- Home

- Gilman, Felix

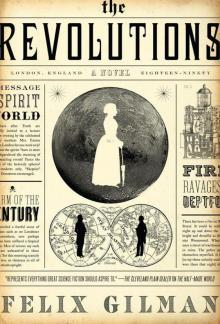

The Revolutions Page 3

The Revolutions Read online

Page 3

“Sad news, Mr Shaw,” Borel said. “Sad news indeed.”

Borel adjusted his spectacles. He looked anxious. Arthur had heard that the Duke had been the landlord for half of London; his death would be as disruptive in its way as the storm.

“The old fellow was in London for Christmas,” Borel added.

“The storm did it,” Sophia whispered. “The noise and the lightning. He was always afraid of bad weather—that’s what people say.”

“Good God,” Arthur said.

If he hadn’t already lost his hat, he would have taken it off.

The fact was that he’d always thought of the Duke, in so far as he’d thought about him at all, as something of a figure of fun. The Duke had been a staple of the newspapers since long before Arthur was born. He was a second cousin—or some such complicated and mysterious relation—to the throne, and it was said that after the Prince died he was one of the very few people whose company Her Majesty could tolerate. In his old age he had become a reformer, an advocate for the education of women, and exercise, and modernization of the prisons, and other more controversial causes. His health was said to be bad; there were stories of rare and dreadful ailments and eccentric remedies, strange foreign doctors, and obsessions with mesmerism and meditation and hieroglyphics and telepathy and reincarnation and spirit-writing and astrology. He’d lavished a fortune on the construction of a tremendous telescope near Hastings, but did it fifteen years ago, when astronomy was not nearly so fashionable as it had recently become. The Monthly Mammoth had published a memorable cartoon—it was pinned up in the Mammoth’s offices—in which he wore a turban, and levitated slightly, while he proposed the transport of convicts to the Moon.

“Her Majesty’s beside herself,” Sophia whispered. “She’s locked herself in the church beside his body, and won’t let the doctors near. They say he used to talk to the old Prince for her—rest his soul—they say—”

Mr Borel frowned. “Do not tell stories, child.”

Sophia lowered her head, scowling.

Borel took off his spectacles. Arthur recognised that gesture; it indicated that Borel was about to raise the unpleasant subject of the money that Arthur owed him. He excused himself.

* * *

Overnight, in one of those sudden reversals that the public mood sometimes experiences in the presence of death, the Duke became a hero of the nation, faultless and universally loved. No one recalled ever saying or hearing a bad word about him. The death was an occasion for national mourning; a brief ecstasy of sudden and rather theatrical grief. Her Majesty—by all accounts confined to her chambers, too heavy-hearted even to get out of bed—set the tone. London’s battered streets unfurled black banners. Flowers appeared on fences, tied with black ribbons. Wreaths hung from lamp-posts. Little shrines appeared in windows. Bells rang sorrowfully through the fog. the Times suggested that it was, perhaps, not too much to say that, in a way, an Augustan Age had passed. At Arthur’s church, prayers were said for the late Duke’s soul and for a grieving nation. Sunday crowds on the Embankment wore black, and even the sellers of roast chestnuts and iced lemonade and apple fritters somehow contrived to do their jobs in a mournful way. All along the cold grey river there were broken jetties and cranes and half-sunk boats, all left where they’d fallen, as if the whole city were in too dreadful a state even to think of doing anything about them.

* * *

The courtship of Arthur Shaw and Josephine Bradman began conventionally enough—if one didn’t count the storm—with an exchange of New Year’s gifts. Arthur bought Josephine a pair of gloves that he couldn’t afford; she sent him a card that was so forward that as soon as she dropped it in the post she blushed to think of him reading it, and immediately decided to refuse to recall what it had said; indeed, it hardly seemed that it was her hand that had written it. He appeared at her office the next afternoon wearing his least-bad suit. She glanced at him only long enough to decide that he looked very handsome in it; then, as she stared down fixedly at her typewriter in something of an uncharacteristic panic, he started to speak. He was—she could tell—inwardly praying for another storm, so that he could strike a properly heroic figure; while outwardly suggesting—as if the idea had just occurred to him as he happened to be walking past—that from time to time he had a little typing he needed done, this or that, and he was thinking of writing a book, as a matter of fact, possibly about Darwin, or a sort of detective thing; but in any case it wasn’t just a question of typing, but rather, since, as she could surely see, words weren’t his strong suit, the eye of a poet might … Almost without thinking she stood, and suggested that they go for a walk to discuss the matter.

The park was full of toppled trees and strewn debris. They didn’t mind. As they navigated the treacherous paths her panic evaporated, replaced by a sort of elation. When evening came she pretended not to notice the cold. They talked about everything except business. They talked about nothing. He came again the next day and they took a different route around the lake, and again the day after.

Passions that could not be acted upon or even uttered aloud expressed themselves instead through signs and codes. She illustrated for him the various meanings that could be found in the folding of gloves, the tip of a hat-brim, flowers. The tapping of gloves on the left hand like so meant: Come walk with me. She’d read it in newspapers and manuals of etiquette. The placing of the folded glove against the left cheek for an instant meant: I consider you handsome. To run one’s finger around one’s hat-brim this way meant yes, and the other way no. To take off the hat and hold it like so was a sign that was not to be invoked even in jest, except after the most careful consideration. When she ran out of signs she could remember she started making them up, and soon they both dissolved into laughter.

That night she wrote a letter to a friend in Cambridge, asking if perhaps she was going a little mad.

There was no one to tell them to stop, no one to disapprove; no one in all of London, or anywhere else for that matter. Miss Bradman’s father was deceased, and her mother had rarely left her bed for the past three years, laid low by nightmares and waking visions of hell-fire; she predicted doom and catastrophe so reliably and monotonously that Josephine had long since stopped asking her opinion on most things, and she did not ask her opinion on Arthur.

They walked together in Regent’s Park, or along the Embankment, arm in arm, for hours. He cajoled her to read him one of her poems. It was mostly about Plato, and about the soul, and about visions of variously brightly coloured heavens; walking through the white forests of the moon, disputing philosophy with the Cyclops in his cave in a red desert. Arthur had always considered philosophers prior to Newton to be more or less bunk, and Heaven as he imagined it was not very different from the Reading Room of the British Museum, or a holiday in Brighton, or a well-equipped transatlantic liner. The words were good, though. It made him wish he hadn’t been such an idler at school. Miss Bradman was actually rather relieved that he didn’t know what to say; she didn’t trust men with opinions about poetry.

They exchanged letters—mostly about nothing at all, expressed in the most florid and fervent terms that convention and the English language allowed. He addressed her, tentatively, as Josephine. She didn’t object. Her friend from Cambridge wrote back to say that it did perhaps sound as if she were acting a little hastily, and Josephine wrote angrily to tell her that it was none of her business after all. They each woke, night after night, thinking of the other, and—as if by some telepathy—knowing that the other was thinking of them.

“Animal magnetism,” Arthur explained to his friend Waugh.

“Magnetism, now, is it?”

“Man is a part of nature, from a scientific point of view, and subject to the animal passions—”

“Passions! Now, that’s more like it.”

(Waugh spent his father’s money fortnightly on a particular prostitute, and called it love).

“I swear to God, Waugh. It’s quite uncanny.”

She told her sister about Arthur, in a letter. Her sister told their mother, who sent a letter, in a scarcely legible hand, warning her of terrible consequences if she didn’t repent and leave London at once. Hell-fire and damnation and et cetera; but she was always saying that sort of thing.

“I wouldn’t worry about hell-fire,” said her friend Mrs Sedgley, who had modern views, and believed in the Spirit World, but not in Hell.

They sat in Mrs Sedgley’s parlour, in the big empty house in Kensington she had once occupied with her late husband. Rain pattered on the windows, and Mrs Sedgley’s cat Gautama rubbed curiously against Josephine’s leg.

“Though a touch of caution might, perhaps, if you don’t mind my saying—”

“I have always preserved my independence, Esther.”

“Of course.”

“Esther,” Josephine said. “Do you believe that two people can … well, that they can share certain thoughts, or dreams, or…” She fell silent, and to cover her sudden embarrassment she reached down to scratch Gautama’s ears.

“Am I to understand,” Mrs Sedgley said, carefully pouring more tea, “that you and the young man—Arthur—have experienced such a … phenomenon?”

“I don’t mean it in a vulgar sense—that is, a literal sense.”

“Certainly not.”

“What-colour-am-I-thinking-of, what-card-am-I-holding, and so forth. But rather…”

“In a spiritual sense.”

“Yes. Well—yes.”

She was in the habit—Mrs Sedgley had introduced her to it—of keeping a journal of her dreams, at least in so far as they had poetic or spiritual significance. Since the night of the storm, she and Arthur had both been visited by dreams of stars, rushing water, roses, and distant mountains—though not always on the same nights—and Josephine had woken on several mornings with ideas for detective stories.

“I don’t know.” She sighed. “I shouldn’t like you to think I’m being foolish.”

“Oh, my dear—never!”

They listened to the rain for a moment.

“Certainly”—Mrs Sedgley sipped her tea—“there may be such a thing.” She sounded a little sceptical. “Between two sensitive souls, who knows what might be possible? I remember when Thomas and I were young.… What does the young man think?”

“Telepathy, he says, or thought-transference.”

“Hmm. He’s … educated in these matters?”

“Not at all. Not until a few weeks ago. But he’s taken an interest now. As soon as they reopened the Reading Room he began studying the journals—the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research and so on. It’s rather flattering.”

In a matter of weeks he’d become conversant in the lingo of psychical research, and could happily discuss—scratching his head, puzzled, as if hoping that some rearrangement of the terms might spell out the answer to a question he could not quite define—such arcane subjects as telepathy, and telekinesis, and hyperpromethia (which referred to a supernatural power of foresight), and psychorrhagy (which referred to the breaking free of the soul from the confines of the body).

“A scholar,” Mrs Sedgley said.

“He writes detective stories.”

“Oh? Does he have a good income?”

She had to admit that he did not, and that it was a source of some concern. The prospect of a literary sort of marriage rather appealed to her; poverty did not; yet the two seemed inextricable from each other.

Mrs Sedgley frowned.

“Is he…” Mrs Sedgley sought with difficulty for the right word. She liked to consider herself forward-thinking and somewhat bohemian, and was reluctant to utter such a conventional thought. “Is he a solid sort of person?”

“Oh, my dear—yes. I can’t quite explain it, but I feel he is the most solid person I’ve ever met; as if nothing else since I came to London has been quite real.”

“I see.” Gautama jumped up into Mrs Sedgley’s lap. “Yes, hello, boy; hello.”

“Does it seem hasty? Not to me. It seems that the storm was six months of ordinary life in one night. I think that I love him, Esther.”

“Yes, Gautama, yes; there’s a handsome boy. Josephine, I think I should like to meet this young man.”

* * *

London in general was in something of an excitable mood. The flood of fashionable mourning for the late Duke carried an undercurrent of morbid—frankly paranoid—speculation. Though rivers of ink had been spilled on the subject of the Duke’s death, the cause remained somewhat unclear. He left no heirs or family. Influenza, the doctors said, but this was widely considered an unsatisfactory explanation. A well-known East End medium declared that the spirits had revealed to her that he’d been murdered—she couldn’t say how. She wasn’t the first or the last. Fortune-tellers (who were ten a penny in London) unanimously held the Duke’s death to be a bad omen. The stars were very bad in general for the coming year.

The police denied foul play. The Duke had been elderly, after all, and frail. Yet rumours persisted. Bombs, a shooting, a poisoning. The body was not displayed. Political motives for the crime—if it was a crime—were hinted at in Parliament, whispered in pubs. The news got out that the police were seeking persons in connection with an investigation; of what, they wouldn’t say. The newspapers recalled the deceased’s various lifelong occult interests, his fraternization with spiritualists and fortune-tellers and practitioners of Eastern religions and—well, you never knew with those sort of people, did you? No doubt the great man had been taken advantage of. A man of his breeding had no defences against the low cunning of common frauds. Was there perhaps blackmail involved, or something worse, something the criminal law didn’t precisely have a word for? High time to shine a light on that netherworld (said the Bishop of Manchester, in a letter to the Times).

The Prime Minister spoke in Parliament, calling for calm. The Times criticised the failure of officials to make arrests, and hinted at conspiracy so vaguely and with such discretion that no one was quite sure what they were saying. Some American and Parisian newspapers, less circumspect, called it murder, though they couldn’t get their story straight as to method or suspects or motive.

A New York newspaper reported that Dr Arthur Conan Doyle had been invited by the police to lend his expertise to their investigation of whatever it was they were investigating, or weren’t investigating. Arthur read it in Mr Borel’s shop one afternoon when he went to call on Josephine.

“Can you believe that?” His own detective story had fallen by the wayside, rather. Between the Storm and Josephine, he’d spared few thoughts for Dr Syme in recent weeks. Still, he couldn’t deny feeling a certain small pang of jealousy.

Borel glanced at the headline. “I can believe anything, Mr Shaw.”

“Well now! Dr Doyle! If that isn’t desperation, I hardly know what is.”

Borel said nothing.

Arthur returned the paper to the window. “What do you think, Mr Borel?”

Borel removed his spectacles and studied them, sighing, as if examining their lenses for imperfections. “Mr Shaw, I have suffered considerable expenses in the storm.”

“I dare say.”

“I have borrowed money to make repairs. I did not like to do that. The sum of money that you owe me is now considerable. I do not like to have to remind you.”

“I know, Mr Borel. I know. But the fact of the matter is I find myself hard up at the moment. The Mammoth owes me money—and the rent must be paid before all else.”

“We must all pay rent to someone, Mr Shaw. I am sorry.”

Borel put his spectacles back on and blinked at Arthur as if he were surprised to see him still in the shop.

Arthur took this to mean that their conversation about money was over. Borel was a decent enough fellow. He didn’t like to rub it in.

Arthur gestured at the newspaper. “What do you think, Mr Borel? Foul play, yes or no?”

“How could I know, Mr Shaw?”

“No smoke without fire. One hopes they’ll catch the villain responsible soon; put things back in order.”

“One hopes. I think there will be trouble.”

There’d already been trouble. In Whitechapel, Jewish windows that had survived the storm were broken by stones. A German bookshop near the Museum was burned, and a Russian businessman was found dead in Notting Hill. The Daily Telegraph hinted that Afghan agents were at work in London, and the Omnibus suspected Indian malcontents. The police raided Limehouse. A lot of Indians and Frenchmen and Irish and sailors and gypsies and fortune-tellers and radicals of various sorts were rounded up and arrested for various petty crimes, but no murderers were discovered by those methods. Astrologers said that the stars promised discord, and that the coming year was a bad one for engagements, business ventures, and childbirth. Mr Borel had forbidden his wife and daughter to go outside.

Josephine and Arthur were oblivious to most of this. London’s bad mood didn’t infect them. They were suddenly out of step with their times: blissfully, almost sinfully so. They spent the winter walking, and writing long letters, and exchanging cards, flowers, gifts, poems, love-notes. Dearest love. My own darling heart, my only, my fondest, my soul. They compared notes on their dreams, and attended lectures. They made plans to move to the seaside, to Brighton perhaps, where Josephine would write poetry in a room looking out on the sea, and Arthur would take the train into London twice weekly to meet with newspaper editors … They kissed in Regent’s Park by the lake, in the spot where the rotunda had been, under the disapproving glare of police officers.

Arthur proposed towards the end of February, at the edge of a half-frozen pond in the park, the words turning crystalline in the cold air as he spoke them. A mere formality by that point; an inevitability. The main impediment to their engagement was that it took Arthur two weeks to get his foster-father to send him his late mother’s ring down from Edinburgh—the old sod dragged his feet, counselling against marrying a clever woman.

The Revolutions

The Revolutions